Alan Turner, Artist of the Evocative and the Odd, Dies at 76

Alan Turner, who drew on Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism and more in acclaimed paintings and drawings that could be humorous, disturbing or poignant, died on Feb. 8 at his loft in Lower Manhattan. He was 76.

The poet Lee Briccetti, his partner of almost 20 years, said the cause was progressive supranuclear palsy, a degenerative brain disorder. He had been in home hospice care for some years.

Mr. Turner’s art was widely exhibited and wide ranging. In the late 1970s he produced mesmerizing paintings of trees “that seemed to square off like fighters or wrap themselves around one another in a claustrophobic embrace,” as Michael Brenson put it in a review in The New York Times.

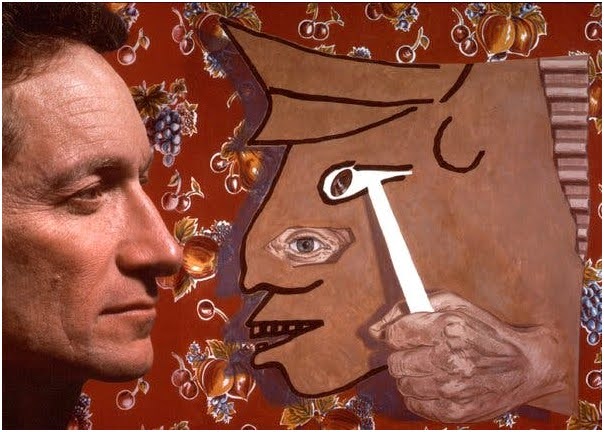

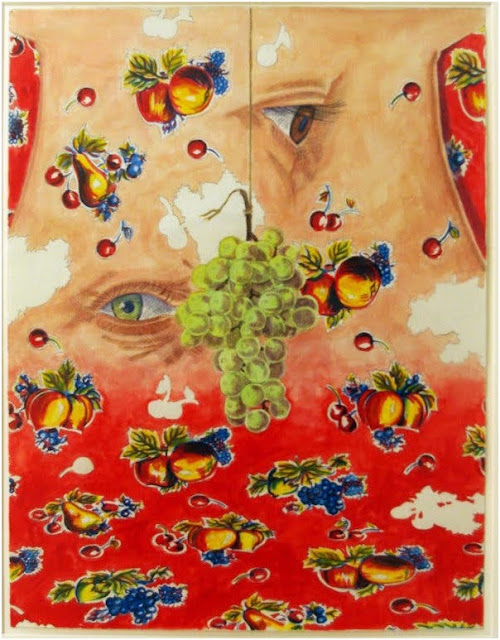

Then came works featuring humanoid figures and faces, the eyes, ears and other body parts distorted or bizarrely placed. “Several noses cohabit on a single torso,” Grace Glueck wrote in The Times in 2000, describing an exhibition at the Lennon, Weinberg gallery in SoHo, “an eye doubles as a nose, and a vaginal cleft seams the long flat chin of a grotesque monster face.”

In recent years, spurred by cardboard shelters in the homeless encampments along the Tiber River that he saw on his frequent trips to Rome, he developed a “Box House” series, mostly in graphite, that explored not only those but all sorts of boxes that harbor all sorts of things, whether people, pets or memories.

Alan Lee Turner was born on July 6, 1943, in the Bronx. “I was to be named after my father’s father,” he wrote in an autobiographical sketch in the catalog for a 2018 retrospective at the Parker Gallery in Los Angeles, “but his name had been Adolph, which did not seem a good name for a Jewish boy to be brought up in the Bronx in 1943.”

His father, Louis, operated the projector at the Lane movie theater in Washington Heights in Manhattan, and his mother, Rose (Taylor) Turner, worked at Stern’s department store.

Mr. Turner enrolled at City College, where he was on the fencing team. He started out as a mathematics major but changed to art, receiving a bachelor’s degree in 1965. He then earned a master’s degree at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1967. The artist David Hockney was among his teachers.

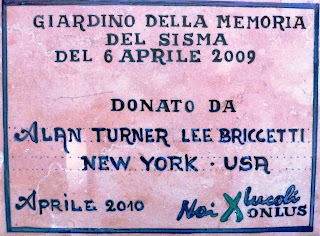

Alan Turner è venuto a Lucoli molte volte, così come all’Aquila ed ha vissuto con noi tutta la fase del post terremoto.

Ha fatto parte della rete di personaggi della cultura stranieri che hanno contribuito a far conoscere all’estero l’esperienza del Giardino della Memoria.

Alan ha passeggiato con noi molte volte per le vie dei borghi di Lucoli, disegnando ogni cosa: i muri, ogni ferita del terremoto, le pietre nude e ogni particolare della vita sospesa che lo colpiva.

Ci ha aiutati quando ci siamo costituiti in Associazione ed ha adottato una pianta di melo nel Giardino della Memoria del Sisma.

Se n’è andato un grande e colto amico sempre interessato alle esperienze italiane ed abruzzesi dalle quali traeva spunto per i suoi quadri.

Grande la sua umanità, grande la sua sensibilità, grande la sua affettività.

Ci lascia un grande vuoto anche se ci rimane la sua pianta che cureremo con grande affetto.

| I frutti del “Melo Cotogno” di Alan e Lee |

Ciao Amico Alan

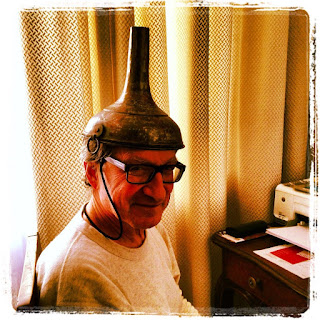

nella foto anche la scrittrice Rose Hayden

nella foto anche la scrittrice Rose Hayden

https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/06/arts/design/alan-turner-dead.html

https://www.artforum.com/news/alan-turner-1943-2020-82396

https://contemporaryartdaily.com/2019/01/alan-turner-at-parker-gallery/

1 comment

Alan was an artist, a Jewish artist, as he was careful and fearless (two more good words for Alan) to point out, who seemed bent on discovering the truth of his own mind, of the way he could see things that others could not: of sex, of culture and of the aesthetics of moral and actual violence. In other words, Alan was a subtle philosopher not unlike his friends John Cage and Jasper Johns. Do we need to note that the truth is not always pleasing? Alan’s images, and even the way they are brushed, and later, drawn, have the look of an artist touching his canvases repeatedly, with control, but with great intention not to make a mark that might live in some zone of painting, but rather to continue the depiction of a thing that needs actualizing. Which is to say, these are not meant to be beautiful objects, but they are real, honest, and gloriously solid. They contain all the information any viewer would need.

Thank you Alan for the gift of your art. Thank you for your friendship.